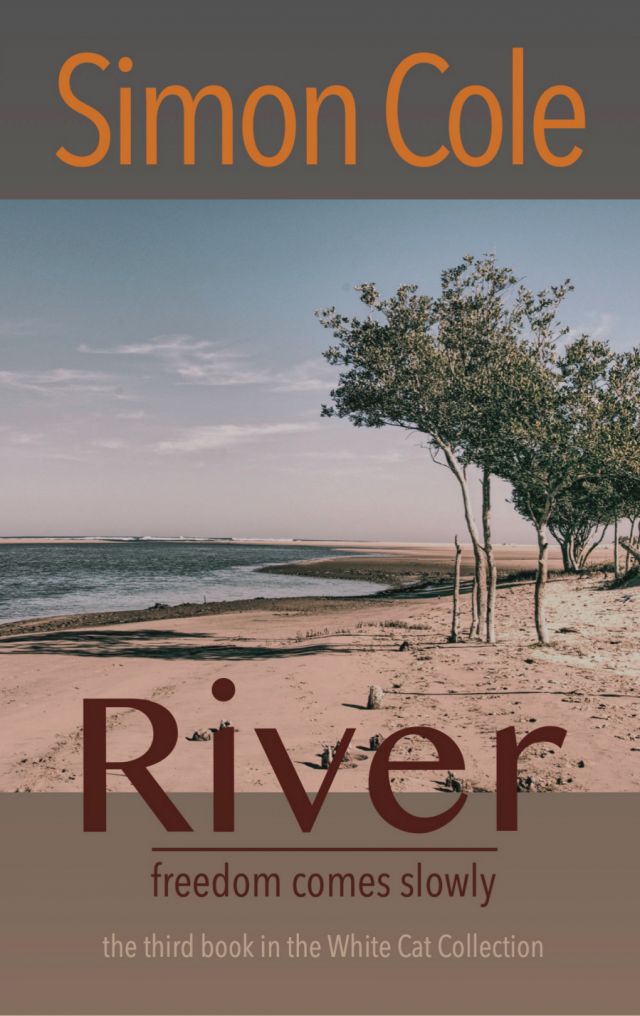

River ... freedom comes slowly

A river flows, lives unravel, paths coincide, cross, conflict…

a peaceful life in middle-class England catapulted into the violent turmoil of apartheid South Africa at its height in the 1970s. The semblance of order will be everywhere in doubt… from the personality of the principle character – one of the post-war under-graduate boom – to the web of State control and oppression in the birthplace of humanity 10,000 miles away.

In the third of the White Cat books the reader will find everywhere the facade of a normality that will surprise and disturb, as it hangs in the balance.

But the glass has shattered before the novel starts, the consequences hidden deep for Richard, or is it Harry? Propelled from the comfort of English academia into the tinderbox of post-Soweto South Africa, his loyalties conflicted over the beautiful Xhosa girlfriend of his doomed colleague, his beliefs challenged at every turn, his escape route blocked, and what he knows of himself, unreliable, the reader travels with him to where his river meets the Ocean, as rivers always must, whoever steps in them along the way.

Purchase RIVER (paperback or kindle) from Amazon here or online (paperback only) at Sumupstore here

Scroll down to read extracts...

“What is your earliest memory?”

They always ask you that, and then you scrabble around peering here and peering there trying to find something, because it’s not exactly the thing you have on the tip of your tongue, so by the time you’ve done the digging the answer you give has probably lost any significance anyway because you’ve likely overlaid it with some false notion of how things were which actually came from somewhere else entirely… but that’s not how it is with me. No. For me the picture is clear and has never changed. I go straight there when I’m asked. And the odd thing is that it’s not because I often go there and look – because I don’t and I wouldn’t, I don’t need to – no, I’ve never looked, but still it’s clear, because, like any part of me, I just know it’s there…

What is my earliest memory?

I think I was just turned four. I was sitting on the grass. It was somewhere like a park, but it was not like a city park with flowers and paths, it was empty, just open space all around. And no people, I suppose my mother had gone somewhere. I must have been scared because I was crying. Then I look round and there is a girl and she is very dark brown with long black hair hanging down her back in a plait. She is just sitting and looking at me, and I see her and I’m not afraid any more. She is saying something over and over like a lullaby. That’s it. That’s all. That’s the memory, it seems like it’s all one thing together – me crying, then not scared, her dark brown, her deep and throaty voice, the words – many years later I discovered that the words, sukhala mntwana, they mean ‘don’t cry little one’. Yes, that was it, my earliest memory. But sometimes when I visit it again now, my mind plays tricks on me and I am asking ‘what is your name?’ over and over. But she just looks.

And then questions appear which don’t seem to fit. Why wasn’t I scared? I can’t ever have seen a black person before – it was the fifties and we lived in a part of the city which didn’t have any black people. It’s like the time has shifted somehow. But I was ok. It was a good memory you see. I suppose my Mum must have come back and found me, and the memory stopped there.

Your turn now.

They will tell you that it’s the Buffalo River, Mbisho mlambo, the feeble trickle oozing out of the sodden ground at your feet. That this is where it starts, 3900 feet up and 78 miles from the Ocean. That it’s the only navigable river in the country. That it was born before there was mankind here, not black nor white, not European nor Chinese nor Indian, not Khoisan nor Xhosa nor Zulu nor Sotho nor Tsonga… before all these, the river came, and started its journey twisting and weaving, finding its way down to soft friendly silt, winding its course around hard rock bluffs, before the trees grew and green-hued the harsh desert tones, before the people came from the north, the descendants of Nguni called Xhosa, but no, they weren’t the first, that was the San, they were here at the beginning, they expected only to live, to be a cell in nature’s great body, a spec on a minuscule planet, the tiniest droplet in the river which will always reach the Ocean.

Of course I had to look into where they were going. It’s a behaviour which follows any loss, our tutor had told us, to find some way to still feel a connection. So, in the library again, and I was looking up East London in an atlas and discovered that it was at the mouth of the Buffalo River… hold on, “Buffalo River”, hadn’t I come across that before? The grave certificate of an ancestor I had found in my father’s ‘Pandora’s box’. For a fanciful moment I wondered whether that was something else that Nobomi knew, another thread, and this one a lot older – that I had an ancestor who had had something to do with the town. And she herself had had a connection with East London. With rivers in mind I recalled that she had told me that where she had found me was at the mouth of a river called ‘Bashee’. I went to the index and after a lot of leafing between index and map trying different spellings, I found it – Mbashe river – about 80 miles along the coast from East London, and I felt a shiver run down my spine. Each of these rivers had its source up in mountains almost 100 miles inland, each seemed to capture its water from a wide upland area, each meandered its way down to the coast twisting and turning through what appeared to be steep wooded valleys and upland planes, each at the end of its course met the Indian Ocean. I became conscious that sitting poring over a map like this – a pastime which had always set my imagination going – the picture which was forming in my mind had an idyllic aspect, it was the picture of a country in an ordered almost pristine view, an earth without the dark shadow of human discord and ugliness. How readily we blandish the dark underbelly. For this was also the land of wave after wave of violent incursion by black and white alike, the land of the enslaving of desperate black families to hard-faced Boer farmers, the land of merciless exploitation of hapless black migrants from ruined farmlands by artful European – large numbers of them British – entrepreneurs, the land of devious manipulation of rural tribesmen into policing fellow-black city ghetto-dwellers, the land of discrimination and segregation and pitiless punishment. It was the cauldron into which my friends had put themselves for love of family and belief in homeland. And now – it was the world with which I apparently had some connection, and into which I was being slowly drawn in ways that I still did not comprehend.

Still nothing said. The white officer walks alongside me, the black policeman walks behind us. Corridors. Stairs. More corridors. This building seems larger on the inside than the outside? Mirrors, no smoke. Was that gallows humour? I’m hoping not, but with each step I have a creeping sense of dread. I have an urge to look round. As if there is some wild creature about to pounce. Nobomi once told me about the mbulu, which are not what they appear to be and… the letters! Have they found the letters? Not Nobomi’s letters, I didn’t bring those, but the Poqo letters. My stomach churns. I feel sick.

“You understand, Meneer Harry, that when we found your possessions your case had been emptied and all the contents were lying around. We collected everything up to return to you. Of course we would see what you had in your case. We found letters posted here in East London to you in England.” He had walked over to another desk and picked up the letters, which had been removed from their envelopes. “They are from Poqo, who are an illegal organisation. We would like you to tell us about them.”

The gloves were off.

There was a deafening crash from somewhere along the corridor, then a scream, but not the scream of a man who has suffered a sudden shock, it was a sustained wail of increasing agony growing louder and higher pitched like an endless screech of glass shattering.

Red, Star. His hands gripped the seat of the chair, knuckles turning white, as every sinew in his body tensed, tightly bracing every limb, his face taut, his eyes, like stone, staring out, beyond…

“Meneer Harry?”

He was waiting to come back. Slowly the room re-assembled in his mind, but now it was evoking no emotion, his feelings disconnected from the sort of fear and foreboding that might have overtaken any other person sitting there.

“Gentlemen, I will tell you what I know, but I must advise you that my information about the letters and what they mean may be less than your own. I have shown them to my doctor in England and even though she knows a little about your country she was unable to help me understand them. Firstly, they do not have my correct address, even though they were delivered to me. Secondly, I do not believe that I am the Mr Harry they are written to because I have never been in South Africa before now and I do not know who Poqo is. I have never known my parents, who are now both dead. I have no record that they were ever acquainted with anyone in your country. These letters themselves were the first contact of any kind that I myself have had with anyone from your country. That is all I can tell you.”

“Then why are you here, Meneer Harry?”

“To return the locket.”

“What locket?”

“In the last letter was a gold locket. I do not understand why you did not ask me about it.”

“Where is the locket?”

“I do not know. It is not among the things you have put here.”

“Then where is the locket now?”

“I have said. I do not know. Everything was taken from me, as you are aware. But it is not here. I cannot tell you where it would be now. You must speak to everyone who could have discovered it between the theft from me and now in this office.”

There seemed to be an uneasy silence around the room after he said this.

“How were you going to find the person who should have this locket?”

“I would go to the address on the letters.”

“There is no-one at that address. We know the house. It is empty.”

“Then there is nothing further I can do in your country.”

“No, Meneer Harry. There is nothing, as you say. But now you must stay until we say you can leave. We will keep your passport. For today you can go. We will come for you if we need you.”

There followed a few formalities – passport, fingerprints, addresses, temporary Pass, letter from the Commissioner, instructions for complying with the regulations – a few formalities, which nevertheless took almost two hours, during which time he was mostly confined to a bare room with a single barred window and offered only a glass of water; then he was escorted from the building and told that buses for the centre of town passed in front. He should board a bus marked ‘Whites Only – Slegs Blankes’.

He didn’t take a bus. He walked. It took him over half an hour to reach the hotel. It had seemed to be a fairly direct route.

... the scene is changing, smaller plots smaller dwellings, but even so some space, some air. I am heading on for Mahlangeni Street. I remember the name scrawled on a wall last time, a long winding dirt road which seemed to run between agglomerations of houses on either side, areas increasingly haphazardly delimited into informal localities by narrower lanes, occasionally a corner vaunting a store or cafe.

There have been people around for a while now, sitting, standing, often groups, women, men, each seemingly in their own domain, talking, or simply watching. Watching me, of course. In the town centre there had been a comfortable enough proportion of white faces, comfortable enough for me to relax into my slightly smug liberal, but feigned, unawareness of any divide. But here I am feeling more challenged. An African in England has to put their hope in our unconcern, but here I must put my trust in their benevolence or, if not that, their passive indifference. Might I be taken for intruder, oppressor, infiltrator, spy? I feel the rub in that, for Emmanuel was my closest friend, Nobomi now my only true companion. But, yes, I am scared. Like most white people in this country. In this country the tables are turned. But everything that I have been, I have left behind. I want to shout that out. I’m not just scared.

There’s a crowd up ahead, along Mahlangeni Street, somebody on a makeshift platform haranguing them, intent faces, this is a mixed crowd and children too. I am not going to be able to creep round the edge, there are too many people and they are crushed right up to the houses; I’m not sure about trying to detour either, though all eyes seem to be on the speaker – tall, authoritative, he would be good in a courtroom – and there are rousing cheers of approval at every phrase he utters, joyous shouting from the women, arms in the air, fists clenched, and it’s getting noisier; he’s on a roll the fellow leading this, trumpeting his message in Xhosa and English, but mainly English, and I’m edging into the crowd, I’m thinking they’re all too absorbed to notice me, as I try to make myself invisible creeping through them, but I am catching odd words the speaker is saying, I hear “Solomon Mahlangu” – he was the headline in the Dispatch this morning, his mother not told he had been executed – and then with vehemence, his voice getting louder all the time, “he told the judge, he told the court, he told the whole world, ‘All we want is freedom’ and he gave us our orders, my sisters and brothers…

At that point the crowd erupted with a roar such as I have never heard before, let alone been in the middle of – AMANDLA. …repeated over and over, STRENGTH, AMANDLA…

There was little sign the chorus was going to abate, but the speaker held his arms in the air to quiet the crowd and little by little the roar subsided enough for him to begin again, now in a gentler tone: “Sisters and brothers, you know we have our own Solomon, our brother in our own town, taken from us for following the footsteps of Stephen Bantu Biko, and he was imprisoned alongside Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu to await his fate, our Emmanuel, a father and his son, my friends, Emmanuel Emmanuel.” The audience indicated recognition. He had been looking around his audience while he was speaking, nodding and pointing with sweeping gestures, and at that point he looked straight at me, though I can only have been a dot in the middle of the dark sea of faces. But the crowd had noticed and a hush was spreading around. I felt caught, trapped by his gaze, like a rabbit in headlights, as if some invisible force was holding me transfixed – could he possibly know? – and then he held out his arm, but he was not pointing as if accusing, his hand was beckoning me to come forward. Faces were turning in my direction and a path was clearing in front of me, so that like the opposite pole of a magnet, I was being pulled towards him. When I reached the platform, he held out his hand and helped me up. Close to, his face seemed vaguely familiar, but now he turned to the crowd who were waiting expectantly: “This is not a fight between Blacks and Whites and Coloureds and Indian, my friends, this is not about British or Xhosa or Zulu or Afrikaner… brothers and sisters, my friends, this must be your belief – umntu ngumntu ngabantu. Murmurs of assent went round the crowd. Then he turned to me putting his hands on my shoulders, and, still audible to the crowd, he said, “My brother, I have to tell you that your good friend Emmanuel is dead and his father too. I will grieve with you, my brother.” He put an arm round my shoulder and turned us towards the crowd as they began to intone uvelwano kuwe, olunzulu.

It seemed as if this might be a ritual which would last a while, but I noticed one of the helpers around the platform leap up on the other side of the speaker and whisper something in his ear. Both glanced quickly across to the end of the road where I had come in, then the speaker covered his microphone and said to me urgently, “Police. You must go. These men will take you where you were going. Peace be with you. Go now.” I was hustled off the stage and immediately surrounded by four helpers who rushed me away in the opposite direction, the crowd parting to give us passage then closing immediately behind us.